This Thursday, 1 December, we’ll be performing a concert at St John on Bethnal Green to mark World AIDS day. We’ll be joined by George Green’s School Choir and Trudy Howson, LGBT Poet Laureate.

This Thursday, 1 December, we’ll be performing a concert at St John on Bethnal Green to mark World AIDS day. We’ll be joined by George Green’s School Choir and Trudy Howson, LGBT Poet Laureate.

Doors Open 6.45pm for a 7pm start, and admission is FREE!

This concert is funded by Tower Hamlets Council in conjunction with ELOP and Positive East. We’ll be singing a sneak preview of songs you can hear in our January concert, SING!

Click here for the Facebook event details.

Blog

Introducing Equivox

Our guest choir at our forthcoming concert, Sing!, is the wonderfully eclectic Equivox choir, from ‘Gay Paree’. (Sorry, couldn’t resist that one). 😉 Established, in 1989, at the Gay Games in Vancouver, the 80-strong choir has been singing chansons for 27 years (making them almost as old as the Pinkies!).

“Zany, fun, friendly, creative is how I would describe Equivox”, says Pink Singers tenor, Liang. “Their presence and staging is second to none. I have performed in a concert with them three times, once in London, and twice in Paris. Some of my favourite memories include doing the conga to “Let the Sun Shine” at the post concert brunch; and hearing the Parisian audience request an encore of “La Mer” which we had sung in our best French accents”.

As Liang mentioned, this won’t be the first time the Pinkies have performed with Equivox. In 2008, they came to London and, we ourselves have traversed the Channel a couple of times as their guests in Paris. One such memorable occasion was in 2009, when we joined them for the ‘Des Voix Contre le SIDA’ (Voices Against Aids) concert. Soprano Tanya tells us more:

“2009 was a busy year for the Pinkies: we performed in two London concerts, co-hosted Various Voices at the Southbank Centre and went on two international trips (Paris in April and Malta in July). The April concert was my fourth foray into organising a Pinkies trip and my second to Paris. This was a little more special though. Why? Well, apart from it being our third performance with Equivox, it was also the first concert any French Health Minister had attended (quite a big deal for our French friends).

‘Des Voix Contre le SIDA’ was in its twelfth year, bringing together other Parisienne LGBT choirs (Equivox, Les Caramel fous, and Mélo’Men ), to raise awareness and funds for HIV and Aids associations. We were very honoured to be part of such an auspicious occasion. 42 Pinkies plus our Musical Director and Accompanist descended on the Trianon Theatre – a beautiful, if somewhat jaded Art Deco building in the heart of the LGBT district, for what was to be a for a fabulous evening.

Worried and anxious faces frantically tried to remember the words to the three (!!) French songs we were singing; radio mic malfunctions beamed backstage nonsense out to the theatre (thankfully only during the dress rehearsal); there were mad Equivox costumes (including a cow, a nun and a Gaultier inspired Madonna, to name but a few); the amazing, frenzied fairy ‘Babette’ (Equivox’s Musical Director) conducted in bare feet on an orange box, and of course, there was lots and lots of laughter.

It was a wonderful concert that received a standing ovation from the Minister for Health (and the rest of the audience), as well as lots of publicity and funds raised for the associations working with people affected by HIV and AIDS. This concert really deepened our connection with Equivox, which happily, continues to grow year on year”.

If our French guests have tickled your fancy, why not come and see both them and us perform in January at Cadogan Hall? Visit our tickets page for more info and book now!

To find out more about Equivox, click here.

Thirty years with the Pink Singers

Last month, Pinkie veteran Michael Derrick celebrated his third decade in the choir. Whilst an active singing (and dancing) member, he has also been the Musical Director (1988 – 1992), accompanist and one of our favourite arrangers. Here, he describes how the choir has (or hasn’t) changed over the last thirty years and what being in the choir means to him.

Last month, Pinkie veteran Michael Derrick celebrated his third decade in the choir. Whilst an active singing (and dancing) member, he has also been the Musical Director (1988 – 1992), accompanist and one of our favourite arrangers. Here, he describes how the choir has (or hasn’t) changed over the last thirty years and what being in the choir means to him.

My first rehearsal was on the last Sunday of October, 1986. It was on a Sunday afternoon because that was the only time the whole choir was free: before the liberalisation of opening hours, pubs closed after lunchtime drinking and didn’t open again until the evening. What else was there to do? Join a choir, obviously.

The rehearsal was in the basement of the London Lesbian and Gay Centre: a dingy space with a low ceiling, out-of-tune piano, no natural light, and the smell of cigarettes and beer from the previous night’s disco. We ‘suffered for our art’. There were about 15 regular singers; all men. The repertoire consisted of show tunes, protest songs, and earnest post-war German cabaret lieder. The other choirs in Europe were into pop songs and classical music but they tolerated our seriousness because we had Margaret Thatcher, Section 28 and an age of consent of 21. They knew that we were “Pink” because that was the colour of the triangle that homosexuals were forced to wear by the Nazis.

The rehearsal was in the basement of the London Lesbian and Gay Centre: a dingy space with a low ceiling, out-of-tune piano, no natural light, and the smell of cigarettes and beer from the previous night’s disco. We ‘suffered for our art’. There were about 15 regular singers; all men. The repertoire consisted of show tunes, protest songs, and earnest post-war German cabaret lieder. The other choirs in Europe were into pop songs and classical music but they tolerated our seriousness because we had Margaret Thatcher, Section 28 and an age of consent of 21. They knew that we were “Pink” because that was the colour of the triangle that homosexuals were forced to wear by the Nazis.

“Every rehearsal was part of a build-up to a concert: a performance and then a new set of repertoire and so on. And at every rehearsal there was the aim of putting on the next concert. So there was a very well defined set of objectives for each rehearsal. That was the choir that I joined and it’s more or less the structure that has survived to this day”.

Thirty years later we are still Pink, still protesting, and still rehearsing on Sunday afternoons; but a lot has changed. Most notably we are a mixed choir. “Mixed” usually means Men and Women. I am proud to say that we are much more mixed than that!

We are bigger, of course, and the repertoire is wider. Early photos show us using music – now everything we perform is off copy; early video shows us standing still or walking about on stage making simple gestures – now we have full choreography. When I go for a health check-up I always tell the nurse that I do a four hour singing and dancing rehearsal each week. This always convinces the nurse that I am keeping fit…

A strength of the choir is the large number of members who write arrangements. In the early days, arrangements had to be written because that was the only way we could perform the songs we wanted to sing. When women started to join the choir, songs were regularly re-arranged to give the increasing numbers of higher voices something to sing. We continue this tradition and it makes us very special – not many choirs do it.

“The first concert I conducted was the first concert the Pink Singers gave with women and men performing. Before that, there were women and men together on the marches, but it was the first concert. And for every single concert since then there has been a range of voices and genders in the choir. And that’s something I’m extremely proud of.”

There have been many other changes over the years but one thing has stayed exactly the same: after my first rehearsal we all went to the pub. The social side of the choir is very strong. It has often been described as a family. Friendships have been made and relationships forged. It has been a complete delight to have been a Pinkie for thirty years.

There have been many other changes over the years but one thing has stayed exactly the same: after my first rehearsal we all went to the pub. The social side of the choir is very strong. It has often been described as a family. Friendships have been made and relationships forged. It has been a complete delight to have been a Pinkie for thirty years.

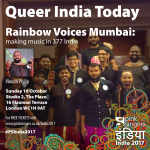

Queer India Today: Identity, Intersectionality and Illegality

2017 sees the 50th anniversary of the decriminalization of homosexuality in England. To mark this important anniversary, the Pink Singers will be running a year-long series of events, focusing on India, where this law remains in the penal code and continues to oppress tens of millions of people.

2017 sees the 50th anniversary of the decriminalization of homosexuality in England. To mark this important anniversary, the Pink Singers will be running a year-long series of events, focusing on India, where this law remains in the penal code and continues to oppress tens of millions of people.

Our first event, last Sunday, was a seminar -“Queer India Today: Identity, Intersectionality and Illegality” – which examined aspects of gay, lesbian and transgender identity in India. It featured some fantastic presentations from three academics from the London-based School of African and Oriental Studies (SOAS) and a special guest via Skype, from Paris!

For those of you who missed it, here ‘s a summary from one of our sopranos, Zoe.

The first presenter, Daniel J Luther, discussed the legal framework behind the criminalisation of homosexuality in India, with particular emphasis on Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code. Section 377 is the Indian law prohibiting same-sex activity, which was drafted by colonialists in the early 1800s to mirror British anti-sodomy laws, repealed in 2009 by the High Court of India, and re-instituted in 2013 by the Indian Supreme Court.

The first presenter, Daniel J Luther, discussed the legal framework behind the criminalisation of homosexuality in India, with particular emphasis on Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code. Section 377 is the Indian law prohibiting same-sex activity, which was drafted by colonialists in the early 1800s to mirror British anti-sodomy laws, repealed in 2009 by the High Court of India, and re-instituted in 2013 by the Indian Supreme Court.

Daniel spoke of the sense of celebration and relief felt in Indian gay communities after the decision to repeal Section 377 in 2009, which prompted many people to come out to their friends and family; the sense of dismay felt after the law was re-instituted; and the hope that despite re-criminalisation, the groundwork for acceptance had already been laid. They also noted that while law reform is important in promoting acceptance of LGBT people, there are still strict social codes in India which condemn non-normative sexuality and gender expression – and that social activism is an equally, if not more important step towards breaking or broadening these codes.

The second presenter, Jacquelyn Strey, spoke about her research on queer female experiences in Mumbai and Bangalore. Jacquelyn spoke of the double social pressures queer women face due to the historic marginalisation of both women and LGBT people in India. In particular, she noted that while gay men are able to freely occupy public space, make connections with each other and move away from home or out of the country to find a safer space to express themselves, queer women are often under strong family pressure to get married, are unable to rent or buy a property without the consent of their father or husband, and isolated from others in their position due to their location outside of the public sphere.

The second presenter, Jacquelyn Strey, spoke about her research on queer female experiences in Mumbai and Bangalore. Jacquelyn spoke of the double social pressures queer women face due to the historic marginalisation of both women and LGBT people in India. In particular, she noted that while gay men are able to freely occupy public space, make connections with each other and move away from home or out of the country to find a safer space to express themselves, queer women are often under strong family pressure to get married, are unable to rent or buy a property without the consent of their father or husband, and isolated from others in their position due to their location outside of the public sphere.

A severe consequence of this widespread social isolation and desperation is that it has become fairly common for young female couples to commit joint suicides, when faced with the prospect of a lifelong sexual commitment to a man. Even female couples who are brave enough to try to run away together run the risk of being detained by the police and the older partner charged with kidnapping or falsely imprisoning the younger one. Despite these ever-present narratives, however, Jacquelyn informed us that there was a burgeoning lesbian social scene in Mumbai, including an activist group called LABIA which campaigns for the acceptance of queer women, no matter their caste, religion, or other social identifiers.

The third presenter, Jennifer Ung Loh, spoke about the “hijra” community in India and the particular challenges they face. Hijras are trans-feminine people who were assigned male at birth, and have historically held a special role in Hindu mythology, serving as spiritual guides for couples hoping to conceive a child. Today, hijras are often rejected from their birth families and form new, tight-knit communities together, organising themselves into strict hierarchies that determine who earns money, carries out household chores and cares for the children. Hijras are dispersed throughout cities and rural areas, and often adopt gender non-confirming children whose parents no longer want them, or street children who need a home. Hijras are universally marginalised and find it extremely difficult to find employment (unless as as sex workers, and more recently, at sexual health clinics).

The third presenter, Jennifer Ung Loh, spoke about the “hijra” community in India and the particular challenges they face. Hijras are trans-feminine people who were assigned male at birth, and have historically held a special role in Hindu mythology, serving as spiritual guides for couples hoping to conceive a child. Today, hijras are often rejected from their birth families and form new, tight-knit communities together, organising themselves into strict hierarchies that determine who earns money, carries out household chores and cares for the children. Hijras are dispersed throughout cities and rural areas, and often adopt gender non-confirming children whose parents no longer want them, or street children who need a home. Hijras are universally marginalised and find it extremely difficult to find employment (unless as as sex workers, and more recently, at sexual health clinics).

Jenny spoke about the difficulties around including hijras in modern LGBT activism, as they are at once more marginalised and more recognised in society than gay men and lesbians. Because they are so visible, for example, they are acknowledged by the government as a group needing support (where gay men and lesbians are not), but they are also completely isolated from mainstream society, unable to work in many professions, and estranged from their birth families.

The seminar concluded with a presentation (from Paris, via skype!) with Vinodh Philip, founding member of Rainbow Voices Mumbai, which is the choir we will be meeting during our January trip. Vinodh provided some invaluable information about being gay in Mumbai, including his own story of making his way as a young gay man in the city.

The seminar concluded with a presentation (from Paris, via skype!) with Vinodh Philip, founding member of Rainbow Voices Mumbai, which is the choir we will be meeting during our January trip. Vinodh provided some invaluable information about being gay in Mumbai, including his own story of making his way as a young gay man in the city.

He also talked abut his decision to start the Rainbow Voices choir as a safe space to sing and express himself after homosexuality was re-criminalised in 2013, and the current functions of the choir today. Vinodh really gave us a taste of the choir, and was very entertaining as well!

It was clear from the speakers’ presentations that the LGBT community in India is extraordinarily diverse, complex and nuanced. Though I was already excited about our trip to Mumbai, the seminar gave me a new desire to learn more about the communities we’ll be visiting, and a richer understanding of their contexts. So… next stop: Mumbai!

National Coming Out Day – A Pinkie Perspective

Our stories and experiences about coming out can change perceptions, create new advocates for equality and perhaps most importantly, allow someone who’s thinking about coming out to take that step. Today, 11 October, is the 28th anniversary of National Coming Out Day. We’re marking it with a story from one of our altos, Zoe, as well as a short video which highlights some Pinkie perspectives on coming out.

Our stories and experiences about coming out can change perceptions, create new advocates for equality and perhaps most importantly, allow someone who’s thinking about coming out to take that step. Today, 11 October, is the 28th anniversary of National Coming Out Day. We’re marking it with a story from one of our altos, Zoe, as well as a short video which highlights some Pinkie perspectives on coming out.

[youtube width=”800″ height=”500″]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D_EMVCEg-oU[/youtube]

Zoe’s story:

“I don’t remember how old I was when I first knew I was attracted to people of my own gender. Truth be told, I don’t think I ever did have that epiphany – what happened was a slow-dawning realisation that not everyone around me felt the way I did.

Of course, I never said anything to anyone. I lived in a small, conservative-with-a-small-c town in Yorkshire in the 1980s and 90s; Queer as Folk and Graham Norton hosting prime-time television were a long way off yet, and it wasn’t smart to talk about ‘being different’. Instead, I listened to rumours about teachers and other community figures that were ‘like that’, read books by E.M.Forster, and avidly watched for queer subplots on Soldier Soldier and Casualty.

By the time I was a teenager, I’d pretty much accepted myself. When my gran told people “Zoe’s too busy to have a boyfriend”, I pretended I didn’t see the knowing looks and just smiled and laughed along. Then I did find a boyfriend – a sweet gay boy, every bit as closeted as I was – and we pretended together that we didn’t notice the surprise and relief from our respective families.

…the relationship, unsurprisingly, didn’t last. Nor did the tumultuous lesbian affair three years later, although both taught me some important life lessons. The first was that I wasn’t prepared to lie about who I was – to myself, or to anyone else – and the second was that I needed to get away from my small town. Being known but not known by everyone there was destroying me, and at that time, getting out was the only way I could think of to fix it.

I went away to university the September of the year I turned 18. I’d cautiously come out to a select few friends and family members over the preceding months, and the reactions had been mixed to say the least, so I couldn’t wait to start afresh. First thing I did was join the then-LGB society (it feels strange to type that now), and found myself surrounded by people like me for the first time in my life. It was a heady feeling, liberating and startling and overwhelming and reassuring all at once. I met the woman who would go on to become my partner to this day, met friends whose struggles and victories became interwoven with mine, and finally reached a place where I felt strong enough to be honest with my parents.

I went away to university the September of the year I turned 18. I’d cautiously come out to a select few friends and family members over the preceding months, and the reactions had been mixed to say the least, so I couldn’t wait to start afresh. First thing I did was join the then-LGB society (it feels strange to type that now), and found myself surrounded by people like me for the first time in my life. It was a heady feeling, liberating and startling and overwhelming and reassuring all at once. I met the woman who would go on to become my partner to this day, met friends whose struggles and victories became interwoven with mine, and finally reached a place where I felt strong enough to be honest with my parents.

That Christmas break, I went home. It was the 90s, and no-one really had mobile phones, so I spent two weeks sneaking furtive phone calls to my girlfriend, and wishing I was back at uni. The whole holiday was filled with tension on my part – I wanted to tell them, needed to tell them, but something kept stopping me. Fear of rejection? Maybe. Whatever it was, I eventually took a deep breath, sat down and told them.

I wish I could say they reacted well. I wish I could say they wrapped me up in a hug and reassured me they still loved me – but they didn’t. They cried and yelled, I cried and yelled, then we all retreated to our metaphorical corners to lick our wounds. I called a couple from the LGB society who were visiting family a couple of towns away, and shakily asked when they were driving back to uni – could I cadge a lift, please, and by the way, did they want to go out and get drunk tonight?

We drove home the next day. By this point my concept of home had already shifted to university, to my girlfriend and friends who accepted me, rather than the place I’d been born and lived the first 18 years of my life. I sincerely thought that I was leaving and never coming back, but some part of my brain wasn’t willing to give up that easily. I loved my parents, even if they couldn’t give me the unconditional acceptance I’d hoped for, and when I got back to uni I called to let them know I was okay. The conversation was stilted and careful, over quickly – as all our conversations would be for the next six months or so – and made no mention of what I’d said or what had happened afterwards.

We drove home the next day. By this point my concept of home had already shifted to university, to my girlfriend and friends who accepted me, rather than the place I’d been born and lived the first 18 years of my life. I sincerely thought that I was leaving and never coming back, but some part of my brain wasn’t willing to give up that easily. I loved my parents, even if they couldn’t give me the unconditional acceptance I’d hoped for, and when I got back to uni I called to let them know I was okay. The conversation was stilted and careful, over quickly – as all our conversations would be for the next six months or so – and made no mention of what I’d said or what had happened afterwards.

Time moved on, as it does, and the raw hurt of rejection settled into a dull ache of disappointment. My parents weren’t bigots, I knew that – so why couldn’t they accept me as I knew they had neighbours and colleagues and friends over the years? Gradually, I started to think about it from their point of view, and how my coming out must have seemed from their side. I’d known I was a lesbian (or at least known I wasn’t straight) for at least six or seven years before telling them. Was it reasonable of me to expect them to readjust their perception of me, every dream they’d ever had for me, without any prior warning other than Nanna’s digs about boyfriends?

Telephone calls were going nowhere, so I sat down and wrote a letter (wow, so quaint and old-fashioned sounding!). I asked them to imagine how it felt to be rejected, not for something you’d done, but for who you are. Who you love. I told them I didn’t want to hurt them, but they’d raised me to be honest, and I didn’t want to keep lying to them over something so important.

A couple of days later, my mum called me. I remember her voice breaking as she told me she hadn’t meant to make me feel rejected, that I was still her baby and nothing would change that, and that she’d been to the doctor to talk to him about what it all meant. He’d reassured her that there was nothing she’d done wrong, that I wasn’t broken (thank you, Doc), and that I’d be okay. I swallowed all my defensiveness and incredulity that she’d gone to the doctor about me, took a deep breath and – we all moved on.

So that’s it, I guess. My coming out story for National Coming Out Day – except it isn’t. It’s one coming out story of the hundreds of times I’ve had to come out during my life so far. Some people have surprised me along the way; some reactions have been better than I’d hoped; some worse than I’d feared. The thing those reactions have in common is that every single one of them has been about the individual, about their prejudices, beliefs and experiences, and not about me. Through them, I’ve learned that there isn’t ever a perfect time to tell people your truth, but that the simple act of getting out there what you’ve known about yourself for years is a release, even when people don’t immediately embrace it.

And the thing is, it really does get easier. That first time – telling your parents, your friends, whoever the big, important ‘first’ is to you – is huge no matter how they react, but you never stop having to come out after that. There will always be a new neighbour, some relatives you haven’t seen for ages, new colleagues or classmates, some random customer service person or healthcare professional… These people will make assumptions about you, and sometimes, you’ll have to correct those assumptions. Don’t try and take responsibility for other people’s feelings: if they’re disgusted or upset or otherwise negative, that’s all on them, not on you. I’m not saying you should be hard-hearted, but you do need to learn what is and isn’t worth worrying about, and trust me, someone else’s opinions on how you should live your life falls firmly into the ‘not worth it’ category.

And the thing is, it really does get easier. That first time – telling your parents, your friends, whoever the big, important ‘first’ is to you – is huge no matter how they react, but you never stop having to come out after that. There will always be a new neighbour, some relatives you haven’t seen for ages, new colleagues or classmates, some random customer service person or healthcare professional… These people will make assumptions about you, and sometimes, you’ll have to correct those assumptions. Don’t try and take responsibility for other people’s feelings: if they’re disgusted or upset or otherwise negative, that’s all on them, not on you. I’m not saying you should be hard-hearted, but you do need to learn what is and isn’t worth worrying about, and trust me, someone else’s opinions on how you should live your life falls firmly into the ‘not worth it’ category.

The main thing to remember is, you’re not alone. Maybe it feels like it in your small town, or your ultra-conservative high school, or your mega-religious family – but you’re not. There’s so, so many of us out here, and we’re (mostly) doing okay. You’ll be okay. It will be okay. I can’t promise you’ll never get a bad reaction for being truthful, but I can promise that in the long run, you’ll feel better about yourself. And that, for me, is the biggest reason to do it”.

For more information, please visit HRC’s ‘Coming Out’ page.